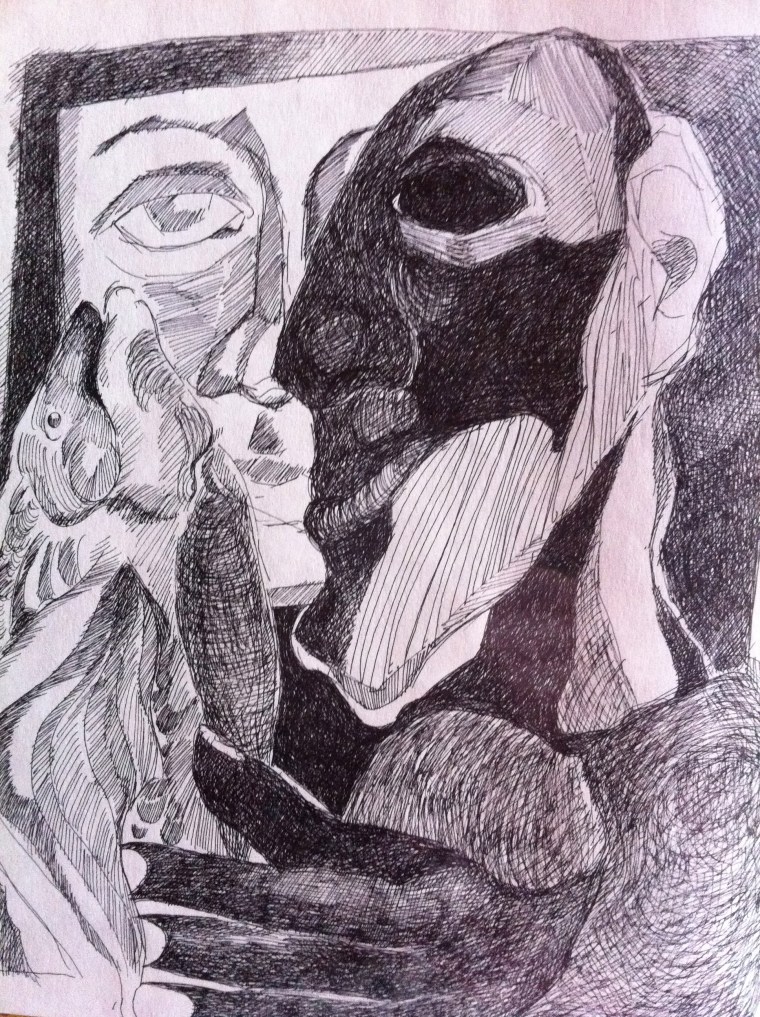

the what is the who

Once, when I was about seven years old, I had asked my mother whether she thought that the idea of me had existed before me, and who could had stored this kind of information and where and how (just to be complete), and she had looked at me with that dreamy look she always gets when she comes up with an idea for a new story. She hadn’t answered me but had rushed over to her desk and started scribbling. You probably know the wacky kids’ book “The What is the Who”. It ‘s still in print. She never answered my question, by the way. Maybe you have to find out some things by yourself.

Once, when I was about seven years old, I had asked my mother whether she thought that the idea of me had existed before me, and who could had stored this kind of information and where and how (just to be complete), and she had looked at me with that dreamy look she always gets when she comes up with an idea for a new story. She hadn’t answered me but had rushed over to her desk and started scribbling. You probably know the wacky kids’ book “The What is the Who”. It ‘s still in print. She never answered my question, by the way. Maybe you have to find out some things by yourself.