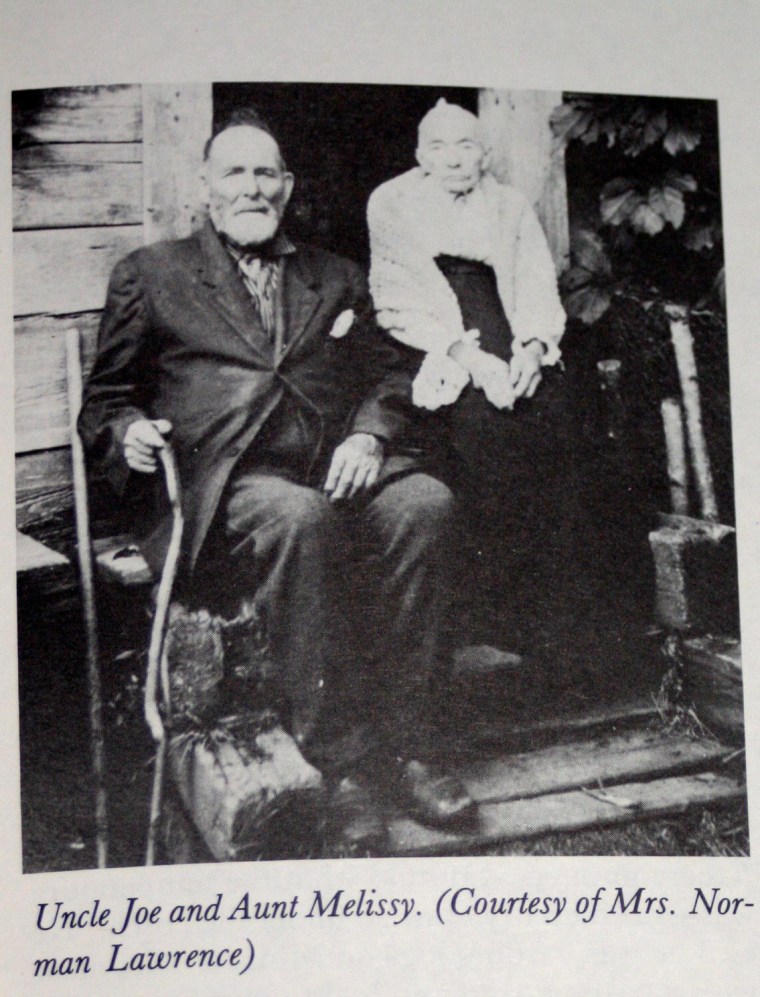

Aunt Melissy and Uncle Joe

Uncle Joe was as talkative as his wife was quiet – but she had a quick wit, accentuating his stories with dry remarks that he returned with good natured smiles. “The smartest girl in the Northern County she was”, he would sometimes say, “and imagine, she agreed to marry me! But only after I cut my beard and swore off tobacco. She would not have had me otherwise, and I have become a better man for it. “

As I started to get stronger and could sit up in bed, still wrapped up in the blankets, Uncle Joe would entertain me with outrageously funny stories of his youth. He was given to enraptured fits of laughter triggered by his own jokes. When he got too carried away with his stories, Aunt Melissy would look up from her work – for she was never idle – and comment sternly: “Never be rash with your mouth, nor let your heart be quick to utter a word before God, for God is in heaven, and you upon earth; therefore let your words be few.” Then Uncle Joe smiled good-naturedly and continued his story with just as much zest while Aunt Melissy continued with her chores as if the words had not been spoken. Only on Sundays she did not tolerate his spinning of tales but insisted on bible study and quiet prayer and he obeyed her without complaint.

I have never again met a husband and wife who seemed so comfortable in their home and so content with their life and each other. Despite his stockiness Uncle Joe was quick to jump up like a cat when Aunt Melissy entered the cottage and eager to please her with some little errand or kindness. She returned his pleasantries with home baked goods and fragrant meals. Her only love besides Uncle Joe were the snow white chicken in her yard for which she was known in the county. Aunt Melissy and her white hens. Children they had none.